Why would you want to work for somebody who looks and acts like the zany gatekeeper from The Wizard of Oz?

It was the early 1990s, and I was just turning 30. I had spent the last three and a half years working at an insurance company as the manager of graphic design. I was in charge of the corporate identity, with a logo designed by the legendary Bruce Blackburn (NASA logo, The Bicentennial logo). I designed an award-winning annual report for the company’s 130th anniversary, launched campaigns for new products, coordinated hundreds of marketing brochures, and handled the annual sales meeting communications. I hated it! It was like being thrown back in high school. This is where all the cliques went! Navigating the company lunchroom was a series of quick decisions: who should you sit with versus who could you sit with? Meanwhile, the real power players were in the Executive Dining Room.

I learned what it was like to be on the client side—invaluable insights that I have used for the rest of my career.

I learned what it was like to be on the client side—invaluable insights that I have used for the rest of my career. I learned how to sell a project internally, I learned how to make an argument for better communications, and how to position design so it aligned with strategy. When I started, the VP of Sales would contact me and ask for a logo, “next week” for a product that had been in the development pipeline for over two years. I learned how to proactively get inside intel by getting cc’d on the right memos. But I was popping Tums to deal with bureaucracy and internal machinations. I wanted to be back on the creative side. I interviewed for a range of positions and thought this one in a small studio where I’d be the Creative Director was the right one. After I accepted the position, a headhunter warned me that this was not a good place to work. But it was too late, I was already committed.

I thought the owner, Michel the Frenchman, with his curly moustache and dazzling eyes, was my ticket out of corporate America and back into the creative design community. He did remind me of the gatekeeper from the Wizard of Oz—he even had a Wicked Witch of the West puppet hanging in the corner of the office. He seemed creative, zany, a bit outrageous, and just what I needed at the time.

I arrived for my first day of work, and Michel was not there. I didn’t have an office, a desk, or a computer. So I went around the studio and introduced myself as the new Creative Director. “Sure you are,” they said. That was not the response I was expecting. I made it through the first week and thought, maybe this is just a one-year transitional job. I wanted to have my own clients, and I had made a deal for commission on anything I brought in. I always knew I was going to open my own studio, but first, I wanted more experience managing and running accounts. My old boss from the insurance company was now at another insurance company and said we could design their annual report. Back then, that was a BIG project. It would take about 4-6 months to complete with fees of about $30,000, which is about $75,000 in today’s money.

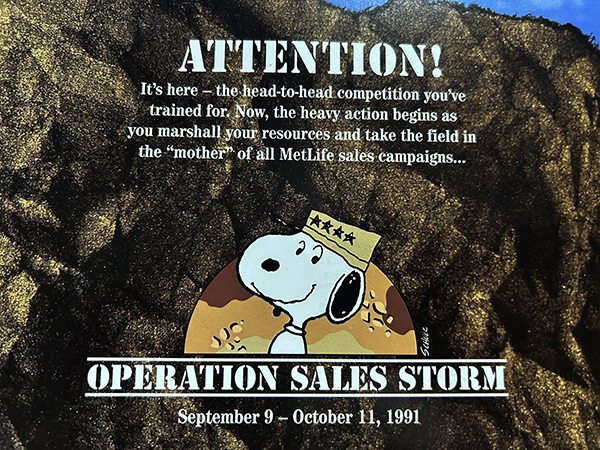

We were tasked with designing a sales meeting campaign called “Operation Sales Storm.”

Michel had one substantial client: MetLife. The design studio was located across from Madison Square Park, where MetLife had its headquarters. Michel would often get a last-minute call, race over to the client’s office, and come back with a new, rush project. Everything was a rush. This was just after the first war in Iraq — Operation Desert Storm — and we were tasked with designing a sales meeting campaign called “Operation Sales Storm.” MetLife had contracted with Charles Schulz to use the Peanuts Gang in all of their advertising. The ads featured a clip of Charlie Brown, Lucy, and Snoopy, and then ended with the catch phrase, “Get Met — it Pays.” The salespeople, mostly men, hated that campaign. They did not want to work for the “Snoopy Company.” They felt it cheapened their products and services. But the public loved the Peanuts Gang. As a cartoonist and admirer of Charles Schulz, I hated the campaign because I thought it cheapened the cartoon characters. Schulz had a knack for capturing authentic children’s voices with pithy wisdom, and now his characters were talking about annuities and term life.

Snoopy was designed to look like he was fighting in Operation Desert Storm for a sales promotion we created for MetLife in 1991.

Now we had to create “Snoopy Schwarzkopf” and put the Peanuts Gang in Desert Storm garb so they could promote sales contests at the annual insurance convention. MetLife promised its sales agents a “head-to-head” competition that would reward them for marshalling their resources. Winners would receive a one-of-a-kind medal with a military-style ribbon that “will add a professional — and patriotic — note to your home or office.” I thought this was so tasteless. I couldn’t believe that Charles Schulz had signed off on this. But it was a job, and we did it.

The studio would be a blast of last-minute MetLife work, with long patches of very little to do. During our downtime, Michel would take us all to the Madison Square Park greens and teach us a French version of Bocci. He did know how to have fun. After a big rush job, Michel and his wife Sylvie would take their twin girls out of school and fly them to Hawaii for an instant holiday. They’d come back with photos of their ziplining adventures. He knew how to spend money.

Sylvie was a partner in the design firm and in charge of office management and new sales. She would bid on new projects and prepare the proposals. She told me she had a secret, sure-fire weapon for closing new accounts. I was all ears—this is why I am here! She whispered to me, “I send out a thank you note after every sales pitch.” That’s it? Doesn’t everybody do that?

The design firm seemed to be just an outpost for MetLife’s sales office. Michel would drop everything, which in most cases was nothing, and dash across the park to get the latest crash and burn project. He would often come back with limited instructions and challenge us to do the best creative work we could. Then he would leave the studio and come back after everyone had left. He would re-work the projects using the info that he had neglected to share with us and tell us we had misunderstood the whole point of the assignment. We would arrive the next morning and see him all shaggy-eyed from his all-nighter, where he was fired up because he had to redo everything. He’d race back across the park and present his designs to the client. Then he would come back, celebrating his own design work and berating the rest of us for not doing anything right. At this point, I started thinking, maybe this is a six-month job.

I had not been there long enough to be responsible for anything going wrong.

Shelley and I had recently been married and decided that this would be a good time for her to go back to school full time. I was to be the sole breadwinner while she attended Bank Street College of Education. It was very important that I keep this job. Yet each day it got worse. I started thinking, maybe this is a three-month job. One day, Michel was blaming me for everything that was going wrong in the studio. I had not been there long enough to be responsible for anything going wrong.

I had to leave the office and get some air. I walked across the park, found a payphone, called Shelley, and told her what had happened. Shelley said, “Quit right now.” I told her I couldn’t quit, we needed the money—I’m the breadwinner! She said she didn’t care, nothing was worth this, and we’d find a way. I made it through the day and headed home. I had one very difficult call ahead of me. I was ready to quit, but I had arranged for my old boss to bring her annual report to the studio. I had to call her and tell her I was leaving. I rehearsed my speech, “I’m leaving, but the studio will take care of you; they do good work, but it’s not a good fit for me, so I’m leaving.” I called my old boss, and she listened to my explanation. She said, “I don’t care about that studio. Why don’t you just take this project and do it yourself?”

That had never occurred to me. $30,000 was a lot of money. I called my designer friend, Norman, and asked him if he’d like to split this project with me. He did, and we designed another award-winning annual report. Norman had been my right-hand man at the insurance company. This was the first project we had done on our own, and it became the beginning of a 20-year partnership in design.

Back to Insights